Yoko Ono at the MCA

Finally saw Yoko Ono at MCA Chicago—an overwhelming, participatory exhibition that redefined what art can be.

Yesterday, I finally went to see the Yoko Ono exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago before it closes this weekend.

I had heard from my husband and friends that the show was incredible, but between the Chicago winter and my own laziness, I kept putting it off. Still, I felt like I couldn’t miss this. As a Japanese woman artist who is internationally renowned—not just in the U.S. but worldwide—it felt like a rare opportunity to see her work presented on such a large scale here in Chicago. So I went.

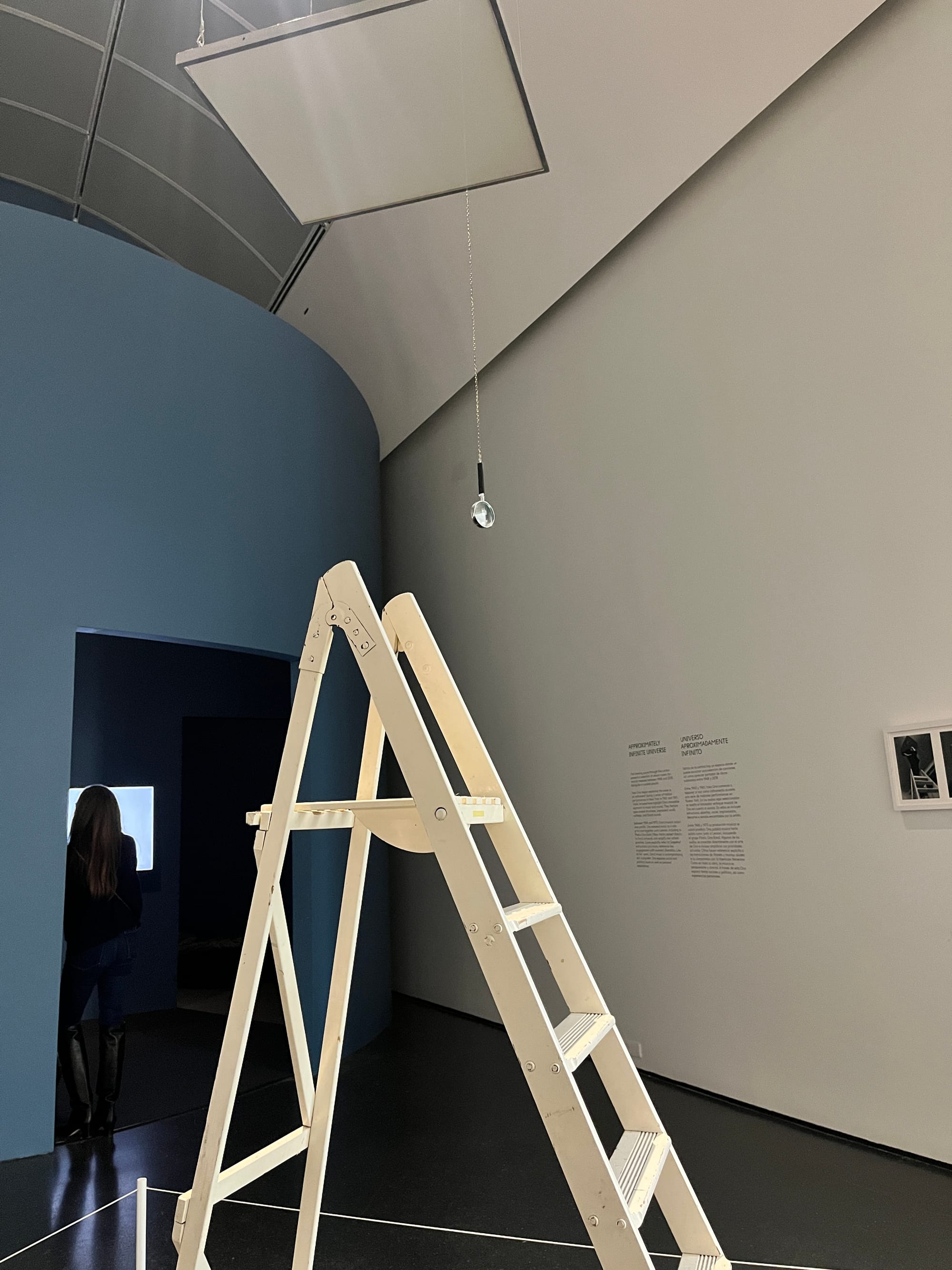

My first honest reaction? She is unbelievably prolific. Of course, she has had a long career, but the range of work was overwhelming—music, events, films, drawings, poems, and instruction pieces. There were many moments where I found myself thinking, “Wait… this is art?” My brain could barely keep up.

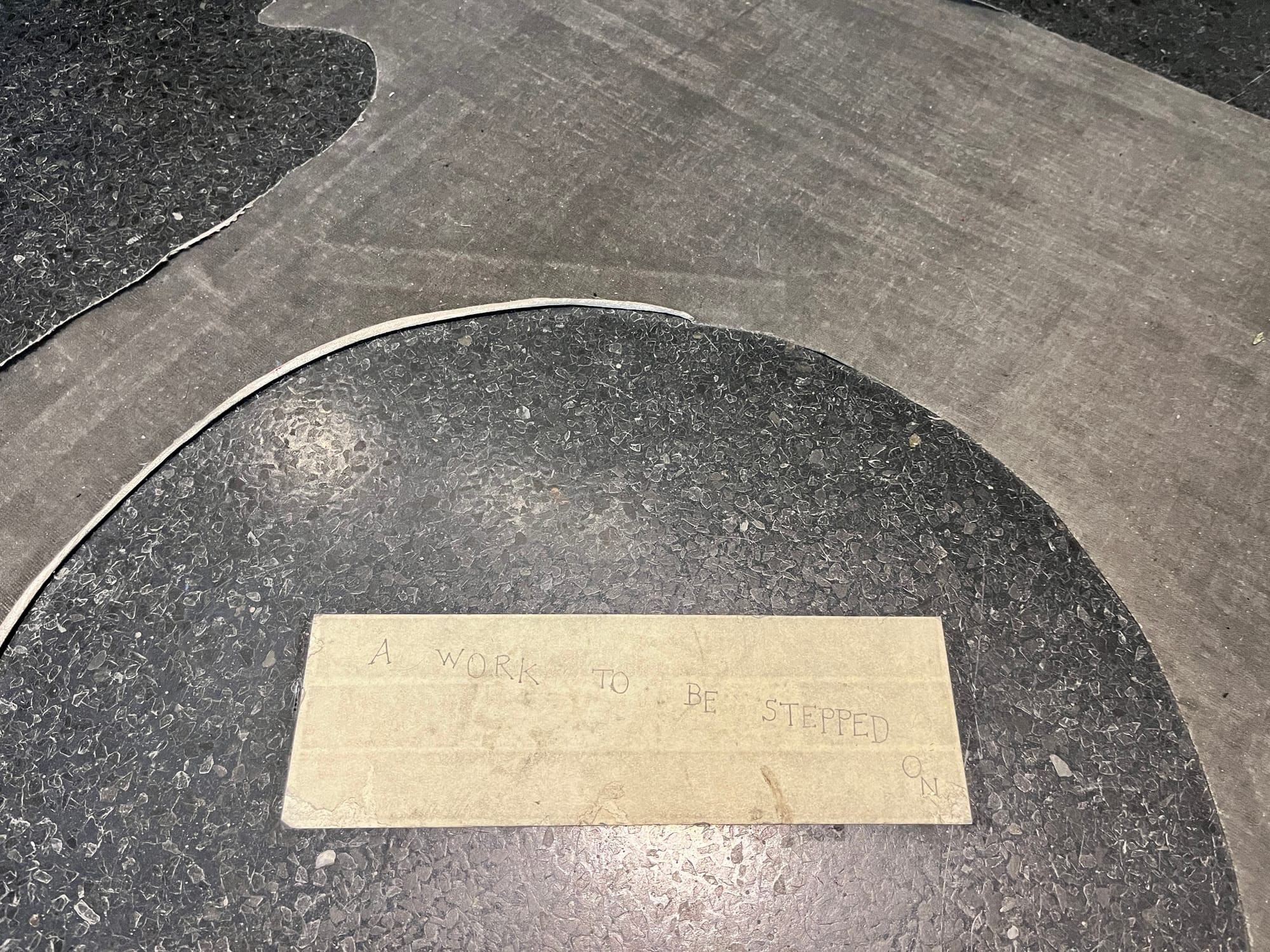

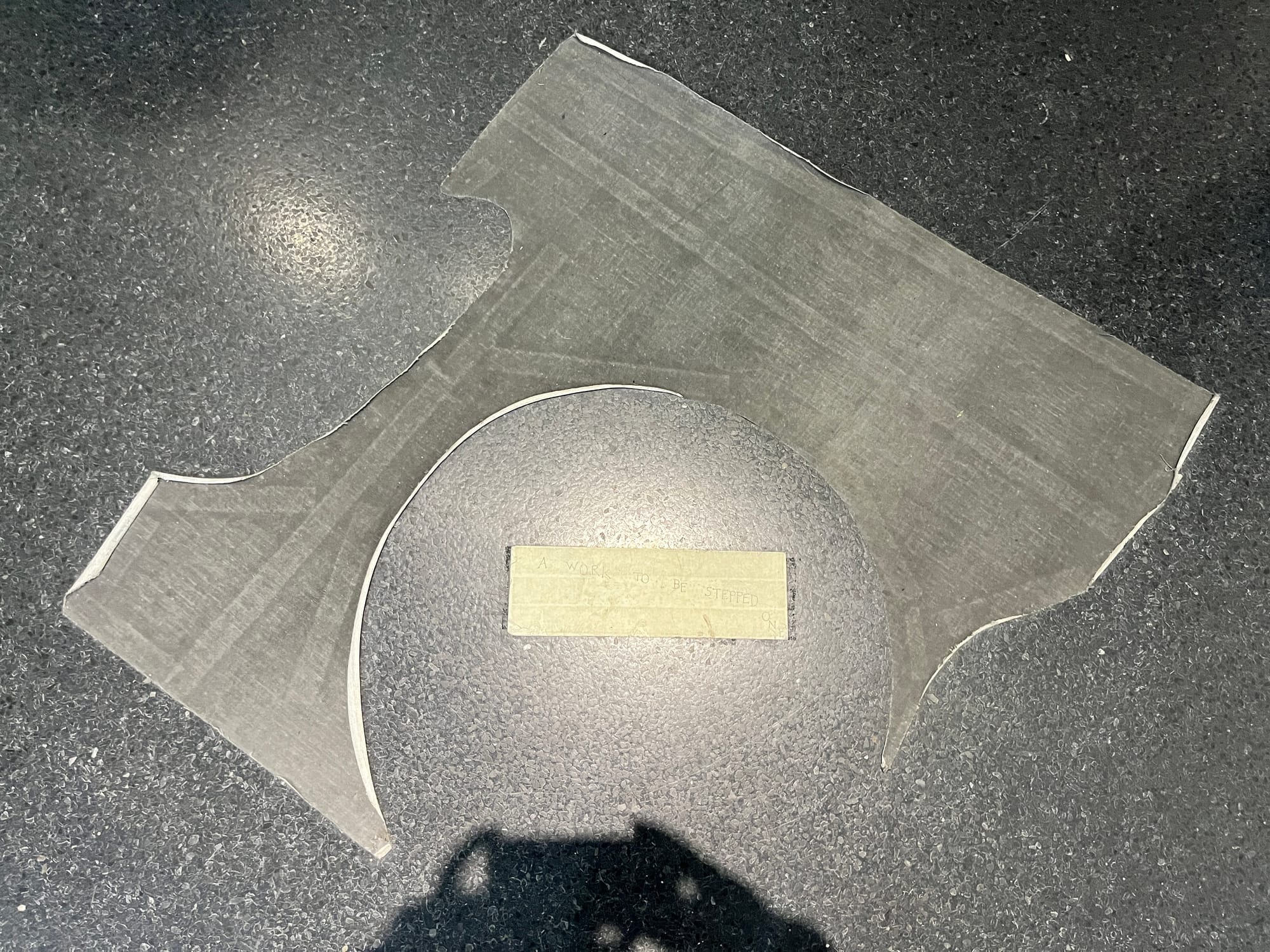

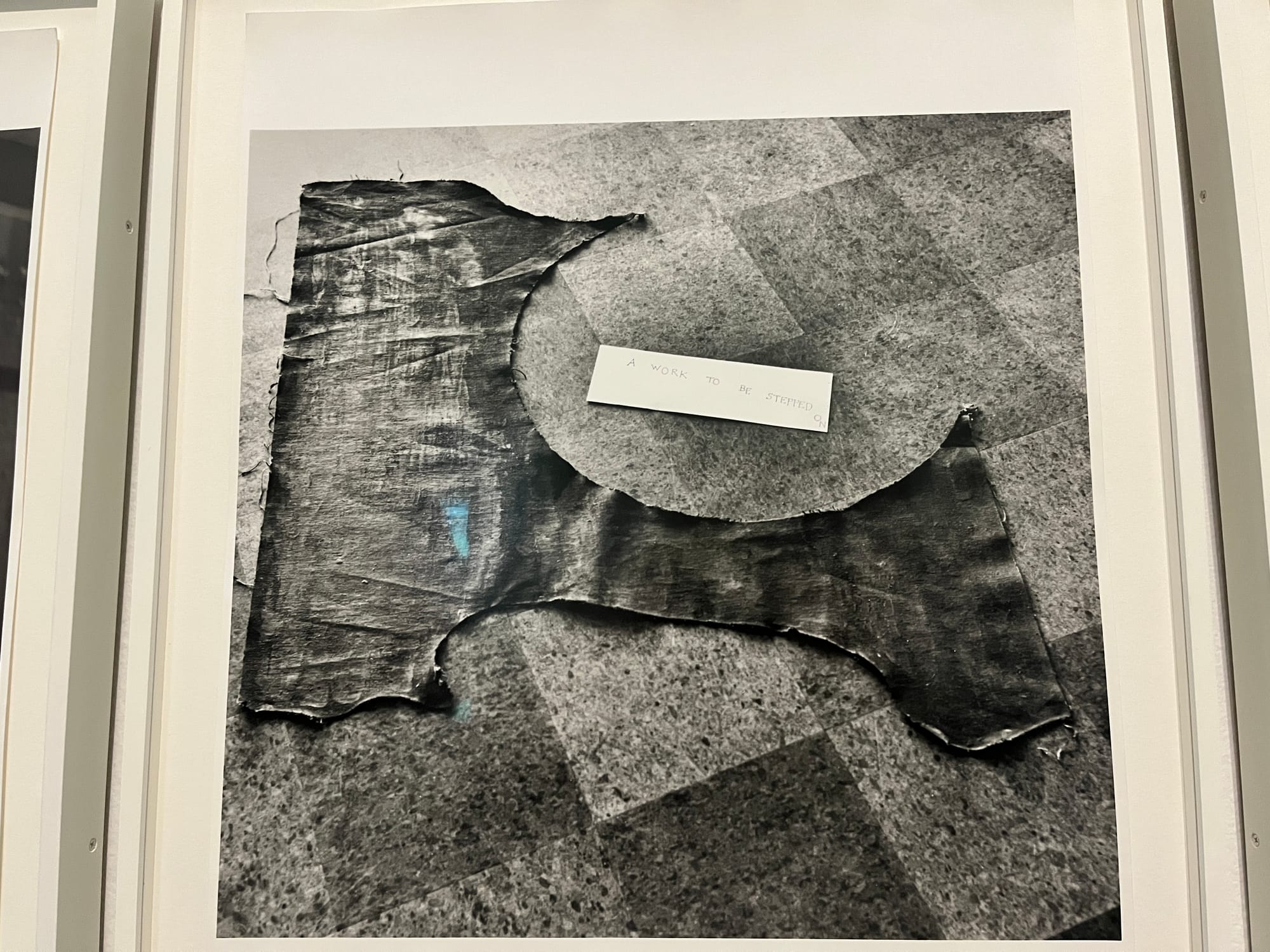

Right at the entrance, I was startled to see A Work to Be Stepped On placed directly on the floor. Apparently, it’s a recreation of an earlier piece she made. It immediately disrupted my sense of how to behave in a museum space.

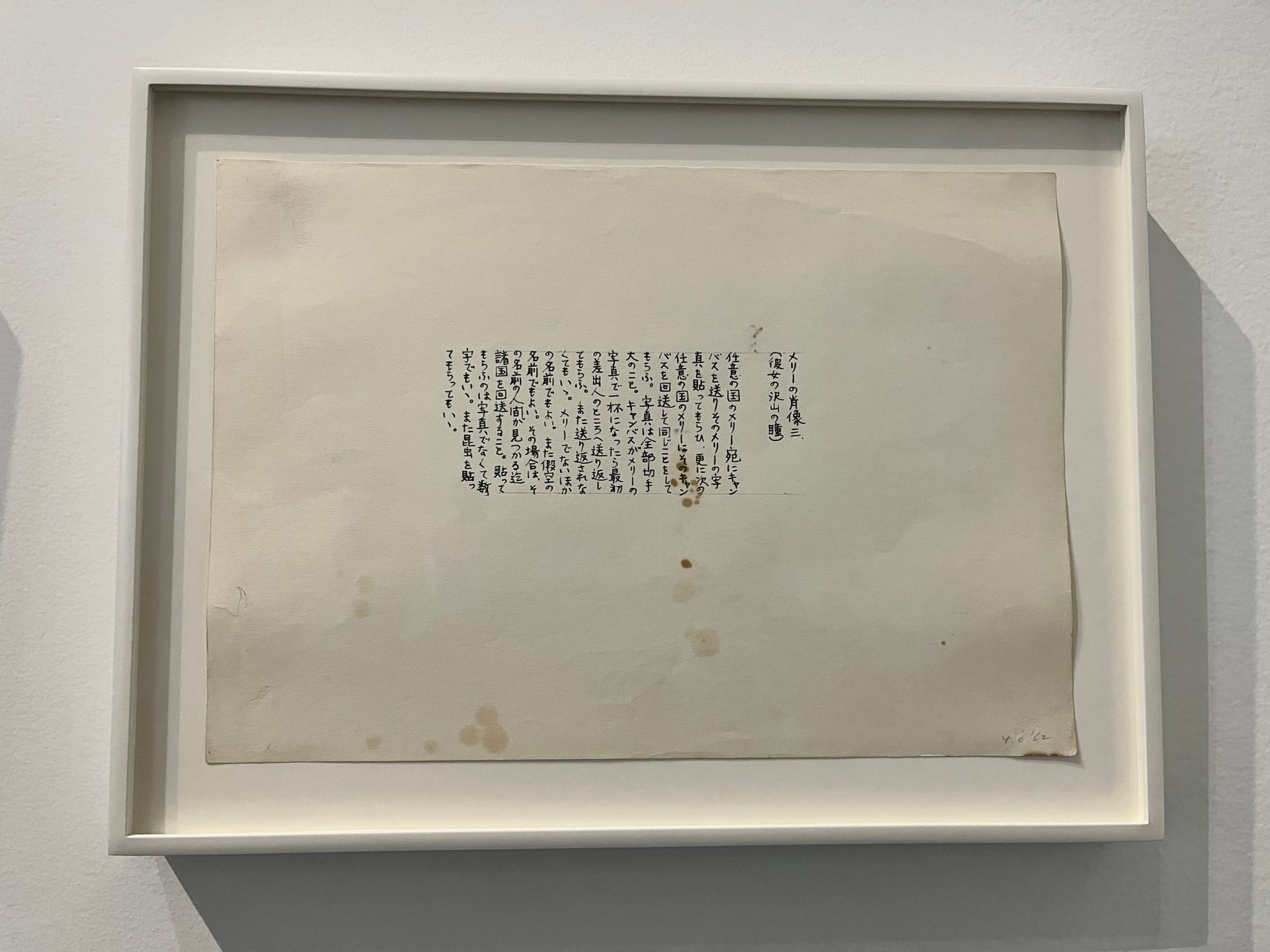

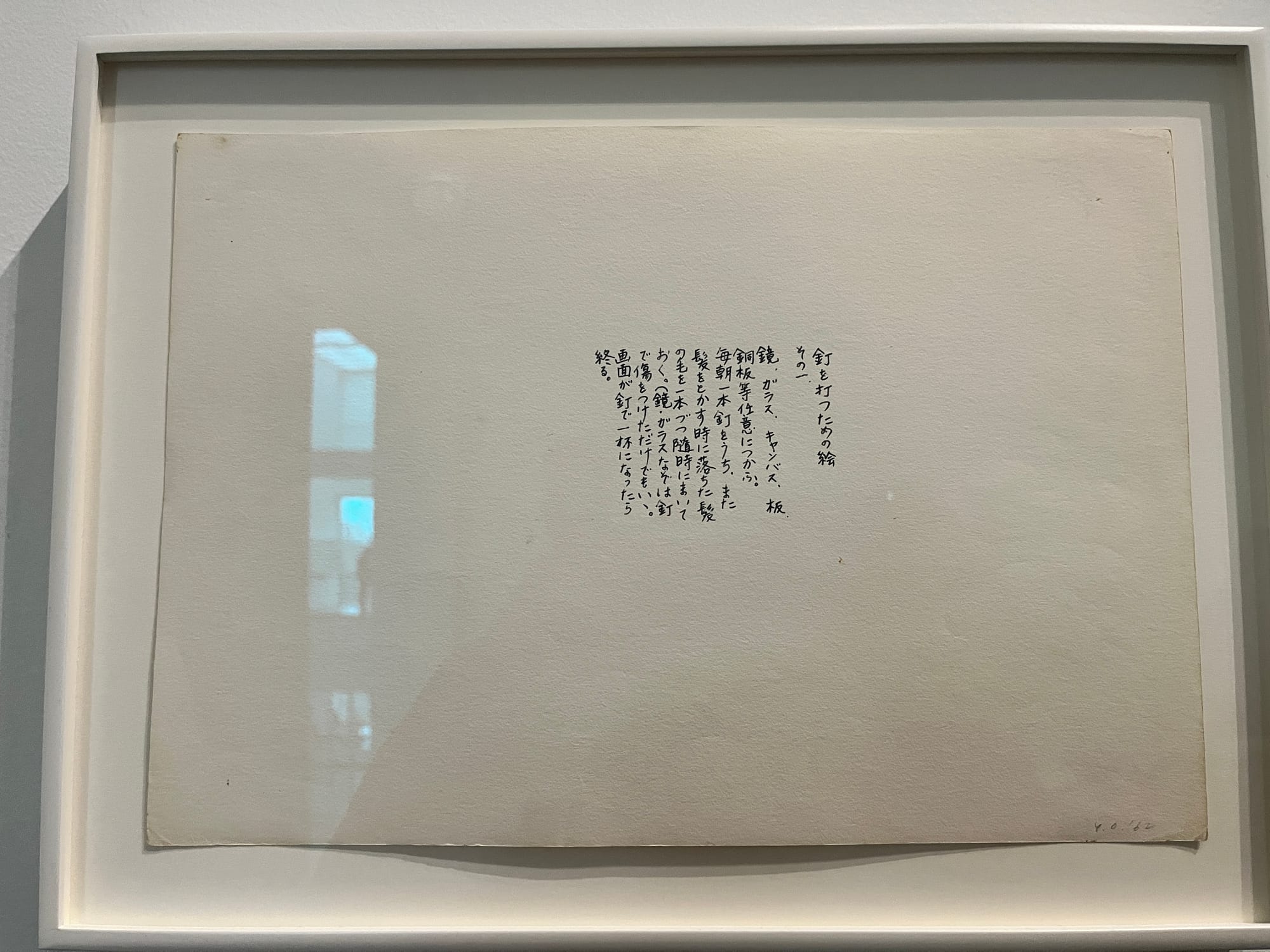

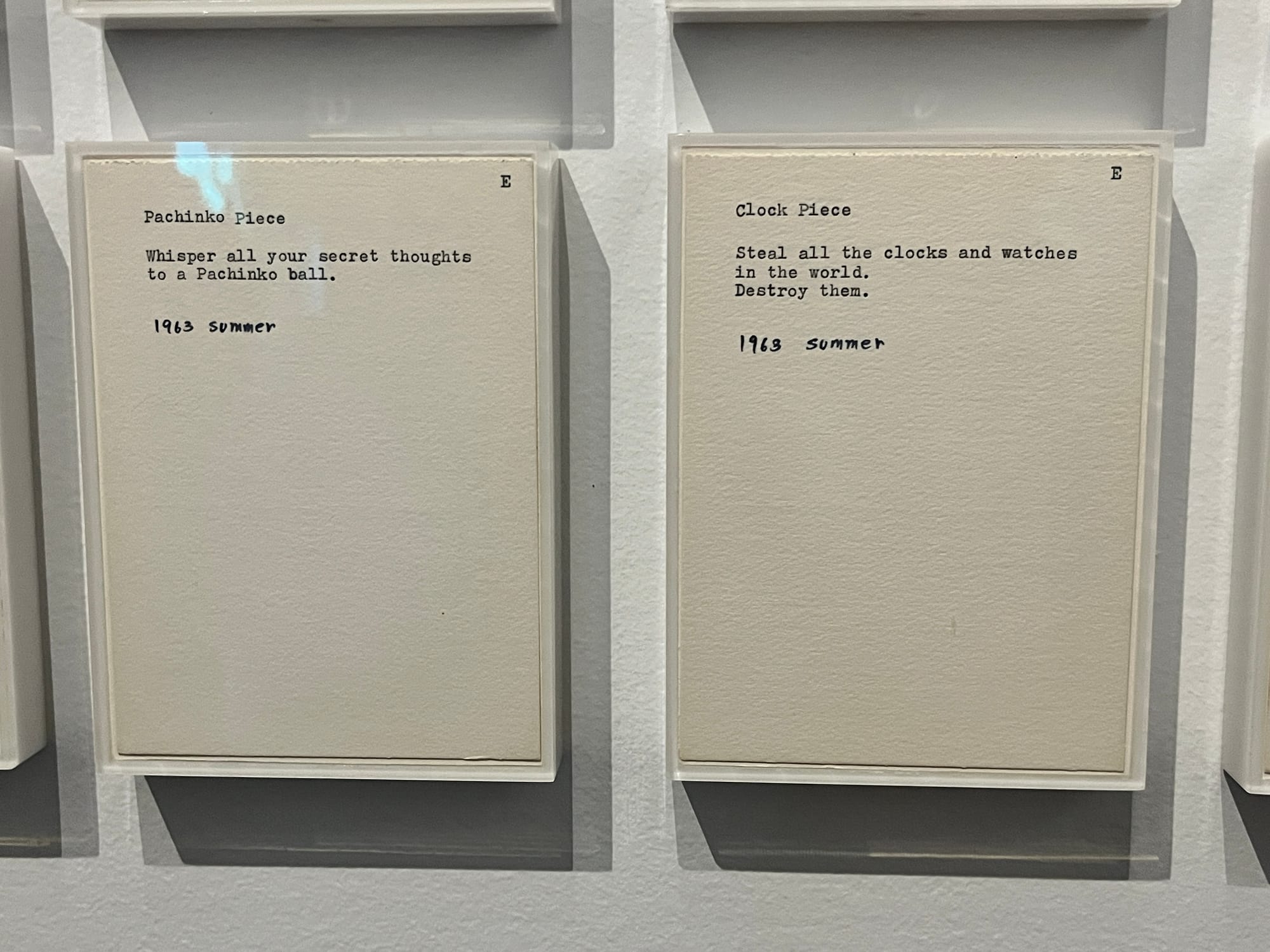

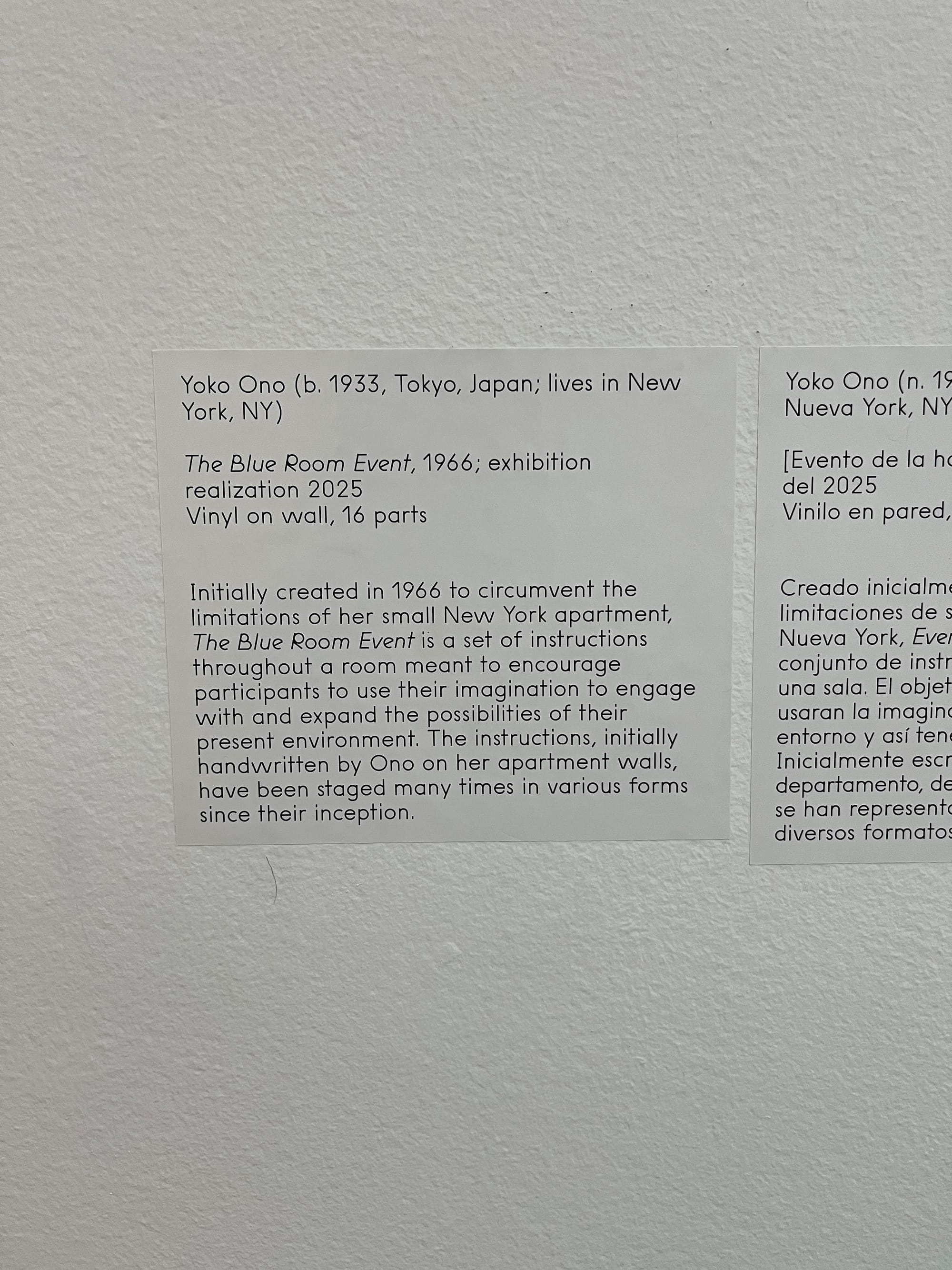

There were also so many instruction-based works. Many of them made me think, “Are we really supposed to do this?” At the same time, the way she wrote and arranged her text revealed a certain meticulousness. It made her feel less mysterious and more human to me.

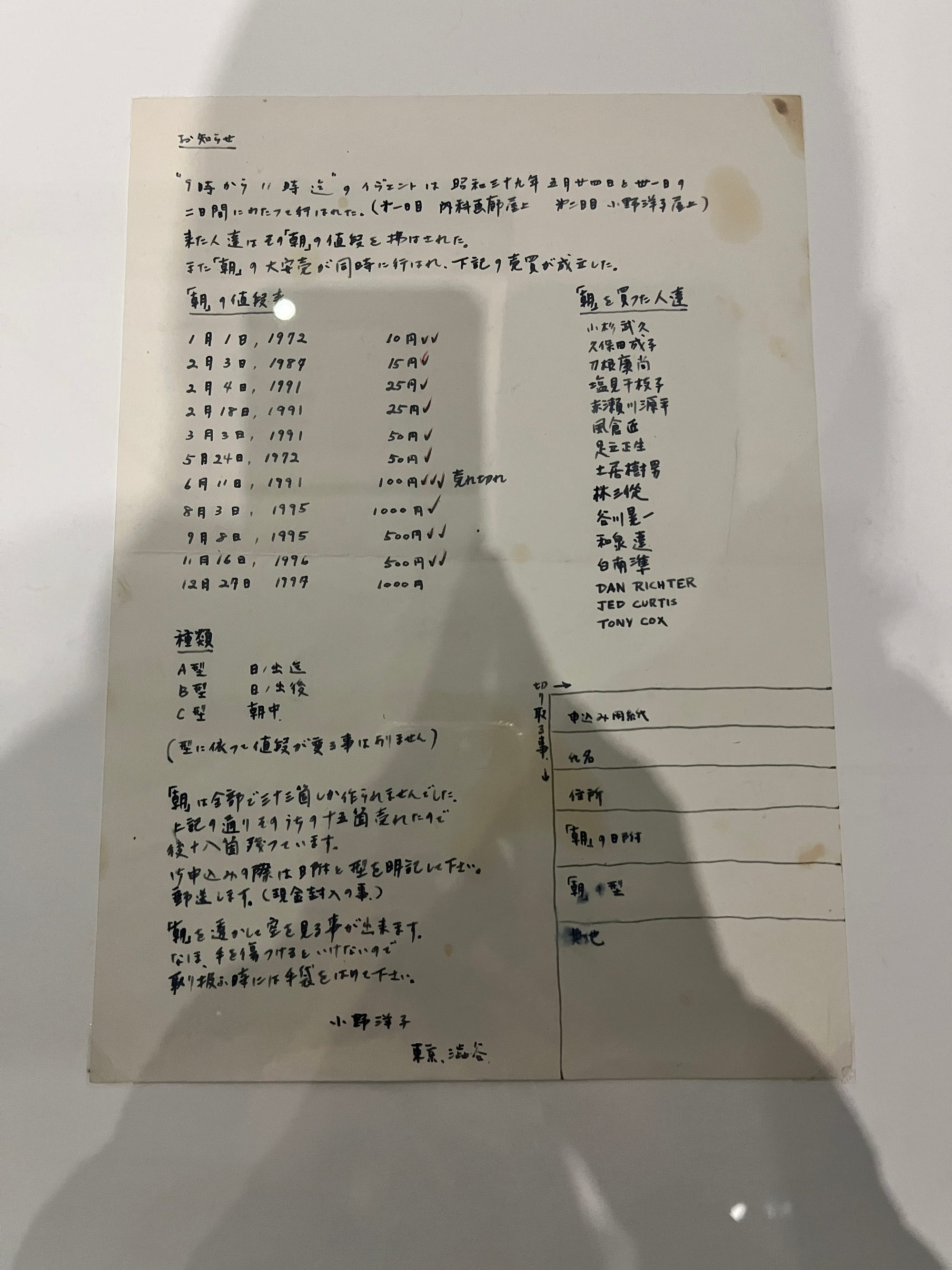

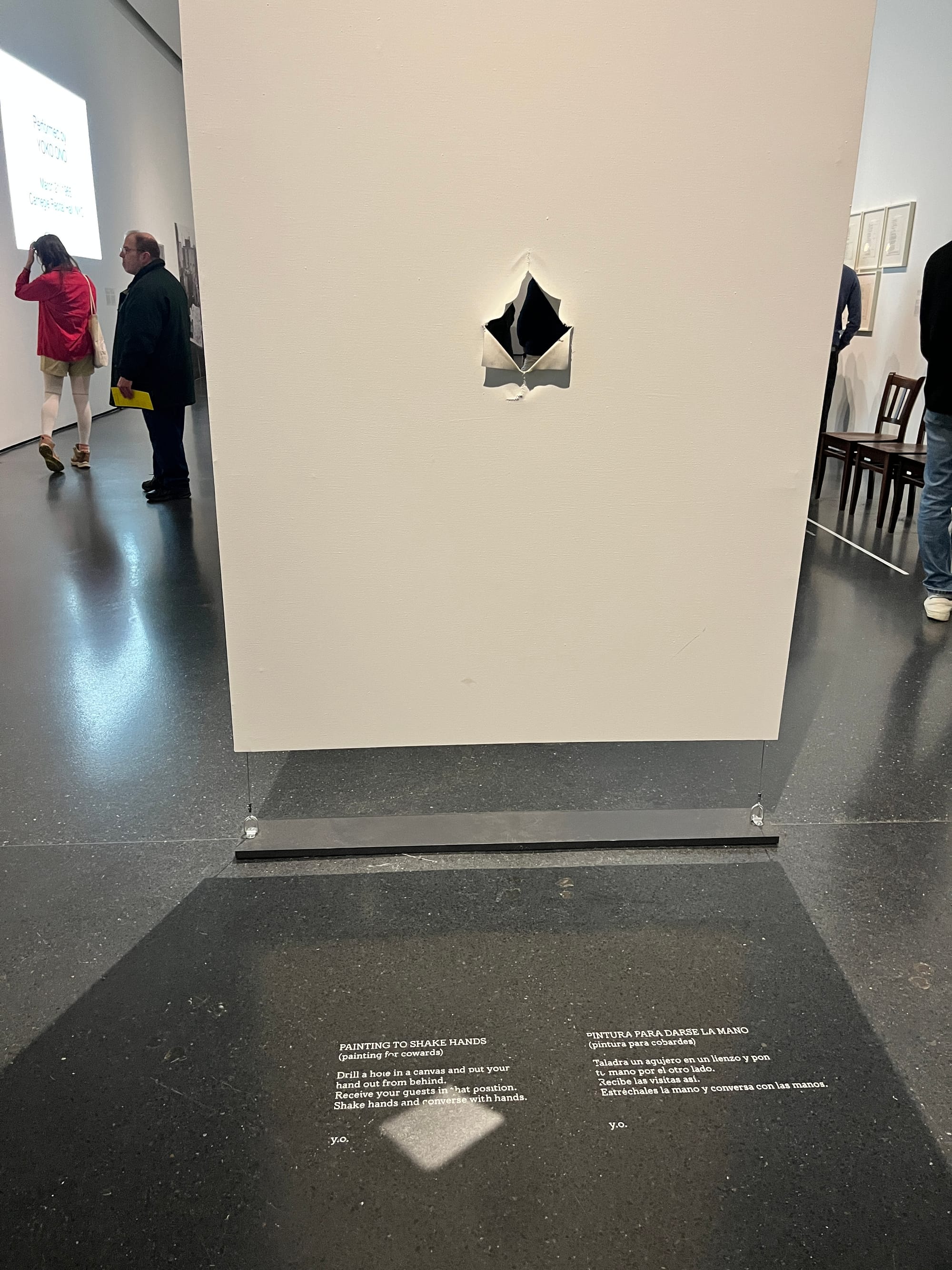

Other rooms invited participation—one space where visitors could freely draw in blue and light blue pen, another where people shook hands through a hole in the wall. There was even documentation (in Japanese!) of her past pop-up action “Selling the Morning.” I was constantly struck by her imagination and boldness.

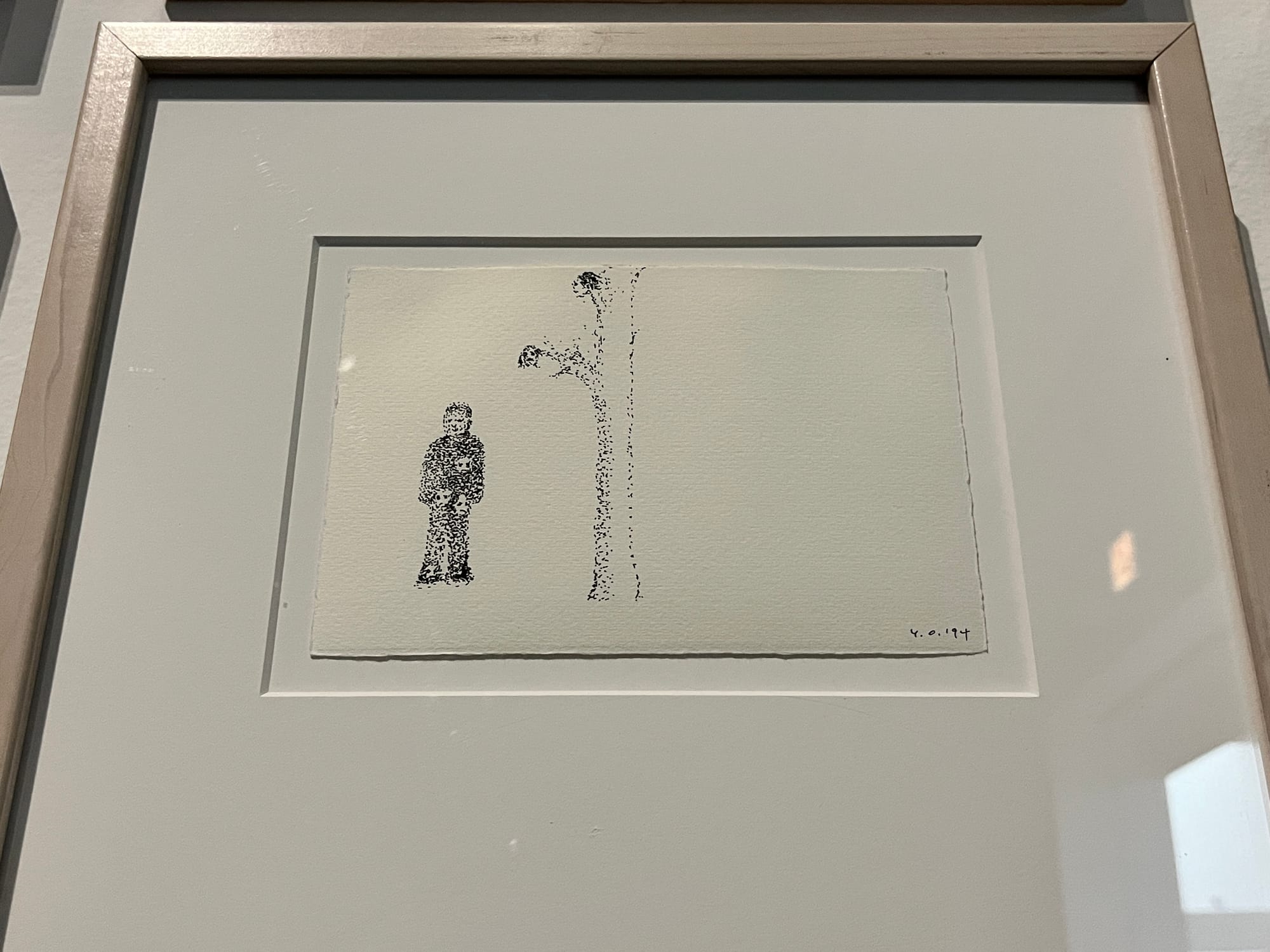

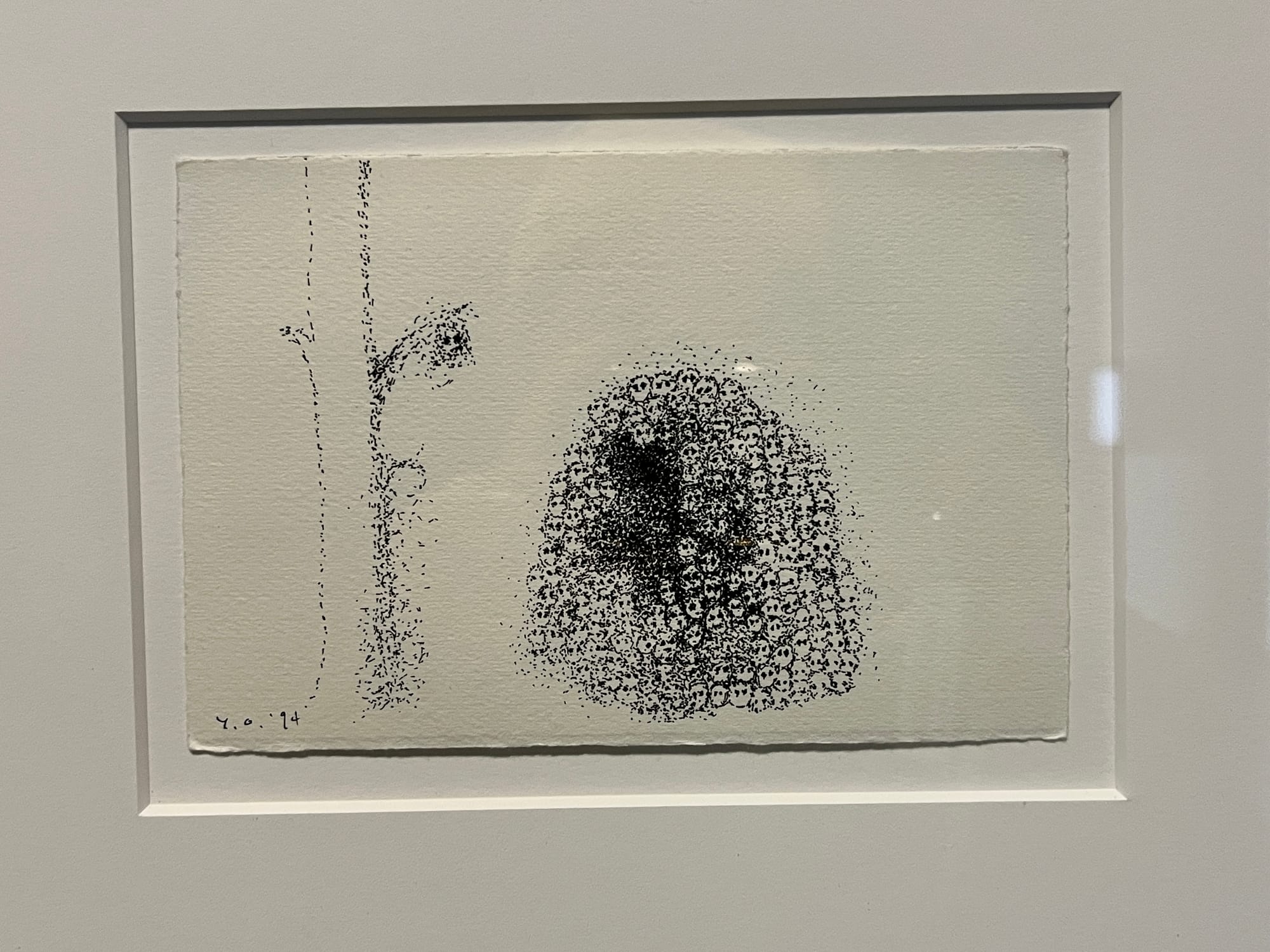

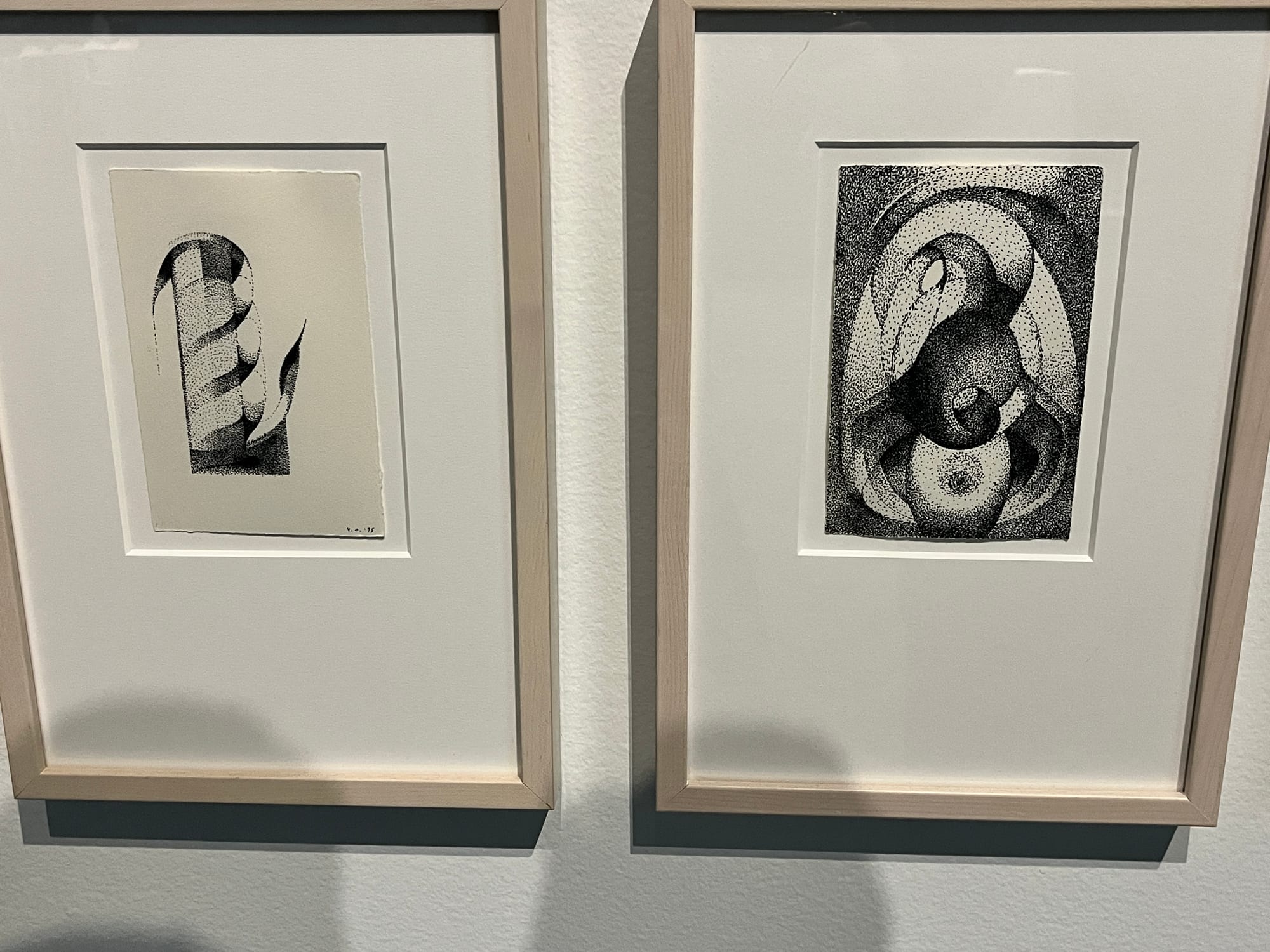

Toward the end of the exhibition, I encountered her dot drawings from the 1990s. Surprisingly, those were my favorite works. I hadn’t realized she drew like that. In my mind, her art had always been large-scale installations and conceptual gestures. Seeing this quieter, more intimate side of her work felt like discovering something new.

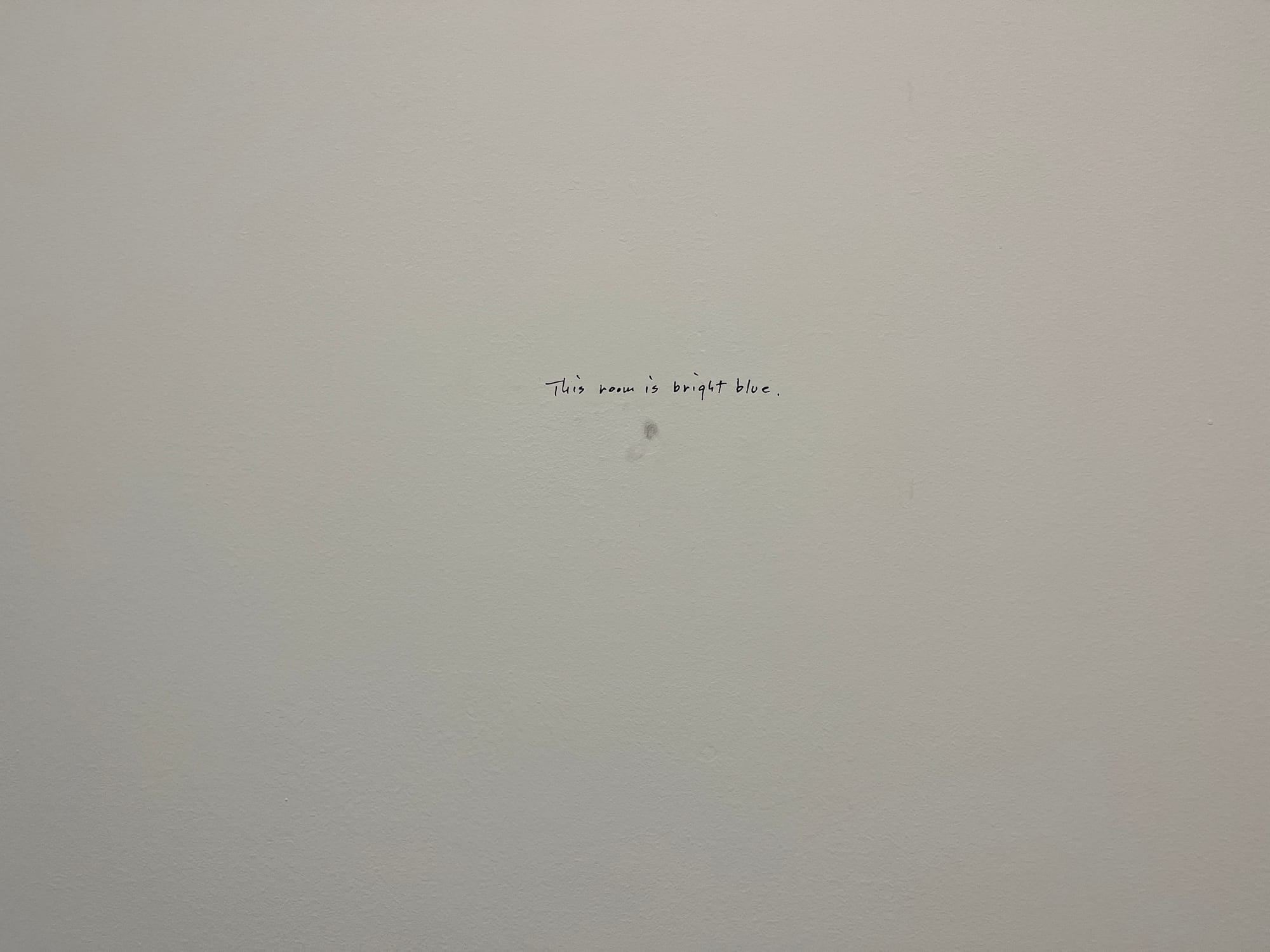

The exhibition concluded in a vast white room filled with handwritten instructions on the walls—phrases like “There is a large window here” or “Please imagine this does not exist.” Watching visitors wander through the space, reading and imagining, felt surreal—like stepping inside someone else’s mind.

I don’t have a neat conclusion. But one thing deeply moved me. I read a plaque explaining that her concept of “imagine” originally stemmed from her experience of war in Japan. During constant air raids, with little food, clothing, or comfort—when survival itself was uncertain—she and her younger brother would look up at the sky and imagine together. Perhaps that act of imagining was her very first artwork.

My grandparents also experienced war as children. I found myself wondering if they too looked up at the sky and imagined something beyond their reality. It made my chest ache. And it made me hope that no one ever has to create art from that kind of suffering again.